Updated Working Paper -- When Fair Isn't Fair: Understanding Choice Reversals Involving Social Preferences

I’ve just posted an updated version of my paper When Fair Isn’t Fair: Understanding Choice Reversals Involving Social Preferences with Jim Andreoni, Deniz Aydin, Blake Barton, and Doug Bernhiem. This experimental paper shows that our theories of decision making under uncertainty don’t explain behavior when social preferences are involved.

The Context

Let’s say you have $10 to split between two poor households, called A and B. The allocation mechanism we’ll use works as follows:

- You say how to split the money, and then I flip a coin.

- If heads: your split is implemented.

- If tails: your split is ignored, and instead the split ($10, $0) is implemented (that is, all $10 to A).

What allocation do you tell me? Pause and think about it for a second!

Most people say that they would choose the allocation ($0, $10) (all $10 to household B). Note than this means both households will get $5 in expectation. Put another way, your giving all $10 to B if heads is flipped perfectly offsets the chance of all $10 going to A if tails is flipped.

Next, suppose I flip the coin and it comes up heads. Surprise! You can change allocation before implementing if you’d like. What allocation do you tell me now? Again, take a second to think about it.

Most people who said ($0, $10) initially will now switch to ($5, $5). This certainly seems reasonable, as now both households are getting the same payment exactly, not just in expectation.

There’s just one problem: these allocation choices are very difficult to justify with our standard models of decision-making under uncertainty.

Note that your decision before and after the coin flip are actually the same choice from a consequentialist point of view. In the first case, I asked you how you wanted to split the money conditional on heads being flipped. In the second case, I asked you how you wanted to split the money once heads had actually been flipped. So if you are a time-consistent consequentialist, you should say the same thing in both decisions.

Our Design

In this paper, we implemented an experiment that was very similar to the above thought experiment, with just one small tweak: rather than allocating dollars, our subjects allocated 10 lottery tickets to the two households. Another set of 10 tickets was pre-allocated by the computer, and one of the 20 total tickets was eventually chosen as the winning ticket. Whichever household had been assigned that ticket would win $10. In this version, the analogue of finding out the outcome of the coin flip is finding out if the winning ticket is in your set of 10, or the computer’s set of 10. If you’re allocating your 10 tickets without knowing if the winning ticket is among them, we call this the ex ante frame. If you’re allocating your 10 tickets and you do know the winning ticket is among them, we call this the ex post frame.

Importantly, we vary the computer’s allocation of its 10 tickets, so that it is not always (10,0) as in the thought experiment we started off with. For example, the computer might allocate (2,8) in one round, (7,3) in another round, and so on.

Why do the experiment allocating tickets rather than allocating dollars? Because in this case the classical predictions are even starker. Let’s assume you’re an expected utility decision maker. Not only would you need to say the same allocation before and after finding out if the ticket is in your set of 10, but exactly one the the following three statements must be true:

- You strictly prefer to give all 10 tickets to household A.

- You strictly prefer to give all 10 tickets to household B.

- You are indifferent among all ticket allocations.

This hold regardless of the computer’s allocations of tickets. On the other hand, from our thought experiment, we expect to see people choosing to perfectly offset the computer’s allocation ex ante; for example, if the computer’s allocation is (8,2), you might allocated your tickets (2,8). This offsetting behavior we call ex ante equalizing. Conversely, we might see people preferring to divide their tickets evenly. This (5,5) allocation is called ex post equalizing.

Results

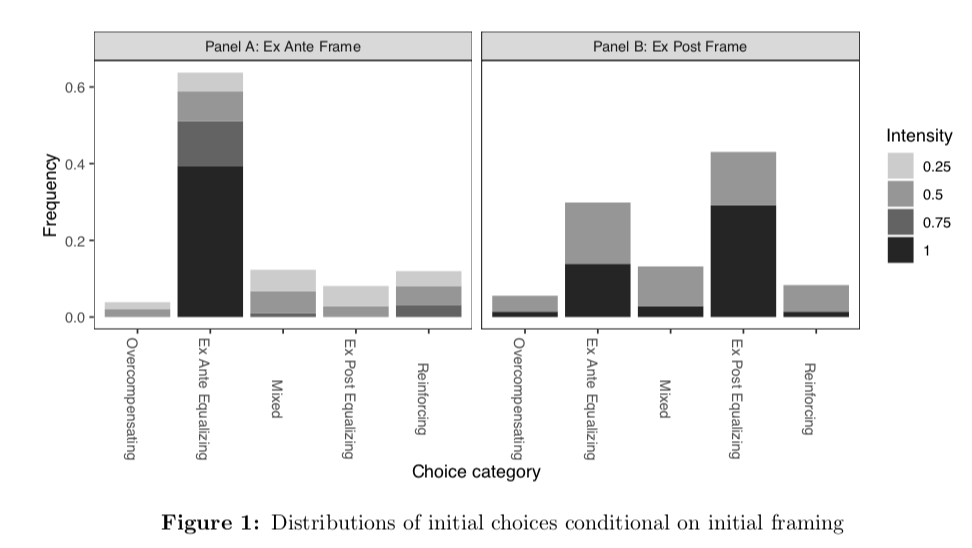

So what behavior do we observe? Across decision tasks, we see that people tend to choose the ex ante fair allocation most often in the ex ante frame, and the ex post fair allocation most often in the ex post frame. Figure 1 from the paper makes this very clear:

These preferences are strict and do not diminish with experience or exposure. (See the paper for how exactly we know this.)

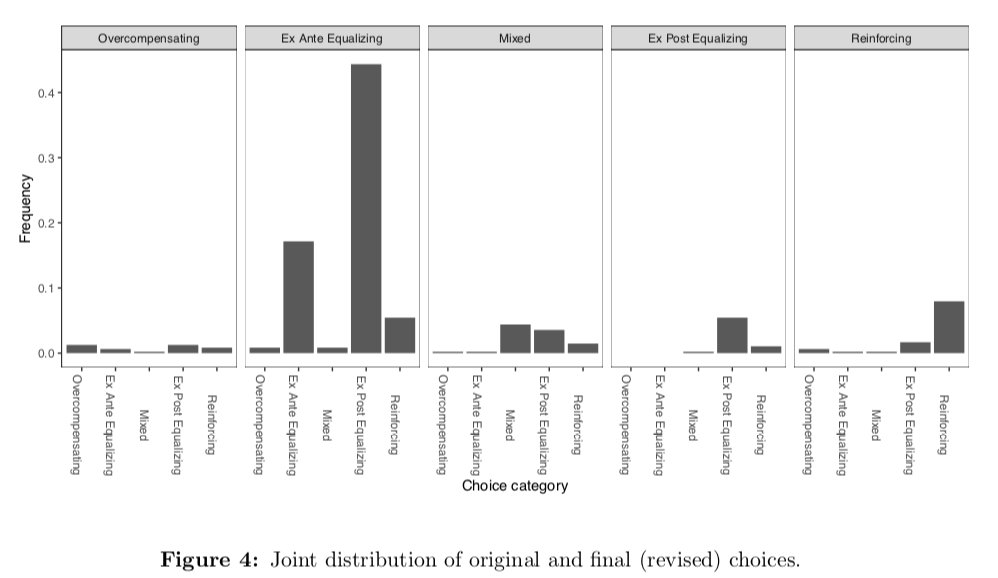

Within decision tasks, we see that choice reversals are common, and they almost always take the form of switching from ex ante equalizing to ex post equalizing. To see this, check out Figure 4 in the paper. In this figure, the panels represent the intial category of the allocation (in the ex ante frame), while the bars within each panel represent the final category (in the ex post frame).

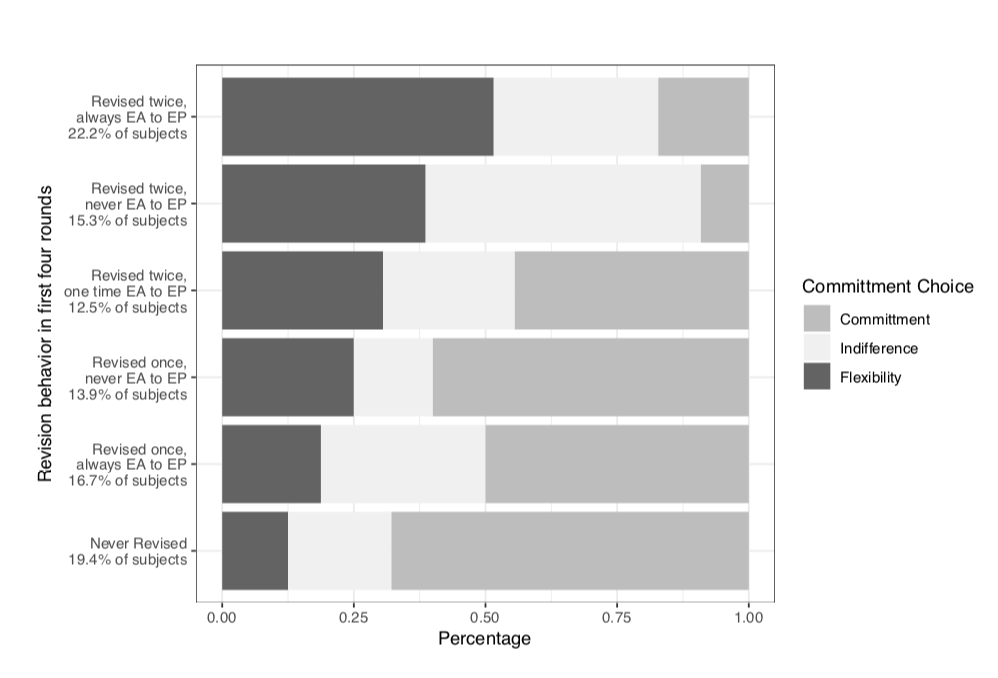

Finally, we ask whether these choice reversals are driven by subjects having consequentialist but time-inconsistent preferences. If this were the case, the subjects who tend to reverse their allocations should demand commitment when offered. Commitment in this case simply means they won’t be asked for their allocation in the ex post frame after having given it in the ex ante frame. However, the subjects who tend to revise often generally choose not to commit themselves:

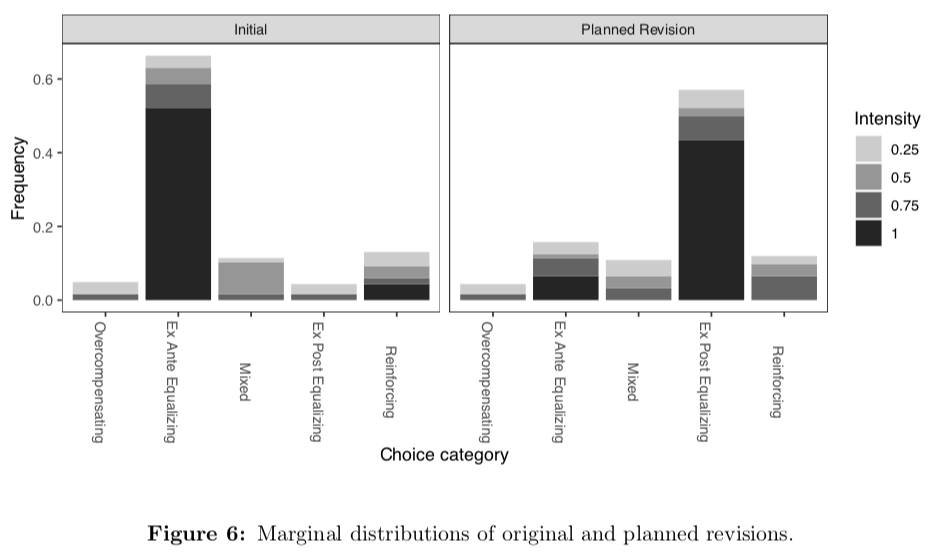

Our second piece of evidence on this question comes from one final treatment. In this treatment, we first asked for allocations in the ex ante frame. Then, before moving to the ex post frame, we asked the subjects if they would like to instruct us to re-allocate their tickets in the case that the winning ticket is in their set of 10. Overwhelmingly, subjects instructed us to re-allocate their tickets in this case to the ex post equalizing allocation, namely (5,5). If reversals were driven by time inconsistency, we instead should have seen subjects sticking with the ex ante fair allocation.

So, what do we think is going on here? Our best guess is that most subjects have non-consequentialist preferences. That is, they may have a procedural definition of fairness which requires choice reversals in this setting. These reversals are not time-inconsistent, since people have preferences over the whole allocation process, not only the outcomes.

If you have any comments, please send me an email, or join the discussion on Twitter